Components#

Reno models are based primarily on stocks and flows. A model is created by defining all of these components and the corresponding equations that make them up.

The equations themselves and how to construct them are discussed in more depth on the Math in Reno page, while this page primarily focuses on the higher level Flow/Stock/Variable components.

Flows#

Flows are equations that define rates of change, or represent how much material/information moves over time.

Flows are created with the reno.Flow class, and the equation can either be

directly provided in the constructor or by setting the .eq attribute later

on:

from reno import Flow, TimeRef

import reno

# create a flow with an equation of "5"

faucet = Flow(5) # 5 units per timestep

# change the equation to vary sinusoidally with time

t = TimeRef() # a TimeRef instance is a special type of variable that

# always refers to the current timestep in the simulation

faucet.eq = reno.sin(t) * 2 + 5

Stocks#

A stock represents an accumulation of material or information, or some quantity thereof over time.

Stock equations are defined exclusively in terms of flows, in-flows (rates of material moving into the stock) and out-flows (rates of material moving out of the stock.)

Creating stocks in Reno are done via the Stock class:

from reno import Stock

tub_water_level = Stock()

Defining stock equations#

Stock equations are defined by setting up in-flows and out-flows. The basic

syntax for doing this uses the += operator for in-flows and -= operator for

outflows:

from reno import Stock, Flow

my_inflow, my_outflow = Flow(), Flow()

my_stock = Stock()

my_stock += my_inflow

my_stock -= my_outflow

A slightly more readable syntax that allows constructing whole “chains” of

in-flow/out-flows can be done with the >> and << operators, where the

arrows indicate the direction of a flow in relation to the stock on the other

side:

from reno import Stock, Flow

inflow, midflow, outflow = Flow(), Flow(), Flow()

stock1, stock2 = Stock(), Stock()

inflow >> stock1 >> midflow >> stock2 >> outflow

Specifically a stock >> flow or flow << stock makes flow an

out-flow of stock, and stock << flow or flow >> stock makes

flow an in-flow to stock.

Chains of these >>/<< operations work because they are

interpreted left to right, and the “return” value of an individual operation

is always the right-most component, e.g. component2 in component1 >>

component2.

As a result,

inflow >> stock1 >> midflow

is equivalent to:

inflow >> stock1

stock1 >> midflow

Implicit stock in-flows#

When an in-flow to a stock is set (either through += or >>/<<)

with an equation rather than just a flow, an implicit flow defined by that

equation is created and applied.

(e.g. if there’s some loss involved between the outflow of one stock and the inflow for another, you could of course explicitly model this with two separate flows as well)

from reno import Stock, Flow

inflow, midflow, outflow = Flow(), Flow(), Flow()

stock1, stock2 = Stock(), Stock()

inflow >> stock1 >> midflow

(midflow - 3) >> stock2 >> outflow

by combining operations together on the same line with commas, you can still do a full chain-like definition when an inflow needs to be a slightly modified version:

from reno import Stock, Flow

inflow, midflow, outflow = Flow(), Flow(), Flow()

stock1, stock2 = Stock(), Stock()

inflow >> stock1 >> midflow, (midflow - 3) >> stock2 >> outflow

Using stocks in other equations#

(This might need to have its own section at the end to discuss the difference between circular references involving stocks and those between flows)

Referencing a stock always refers to the stock’s value in the previous timestep. This allows a form of circular reference between stocks

from reno import Stock, Flow

my_flow = Flow()

my_stock = Stock()

my_stock += my_flow

my_flow.eq = 10 - my_stock

In this example, my_stock is incremented by the value of my_flow

in the current timestep t, while the value of my_flow for timestep t

is 10 minus the value of my_stock in timestep t - 1.

In other words, the equations for these would translate to:

my_stock(t) = my_stock(t-1) + my_flow(t)

my_flow(t) = 10 - my_stock(t-1)

Variables#

A variable is any other equation or value that can be referenced in flow (and other variable) equations and helps define the user-settable model parameters. Variables should be used to specify what can be modified about a simulation/what values you want to experiment with.

coffee_process = reno.Model(steps=10)

with coffee_process:

drip_speed = reno.Variable(3.0)

water = reno.Stock(init=100.0)

coffee = reno.Stock()

coffee_machine = reno.Flow(drip_speed, max=water)

water >> coffee_machine >> coffee

In the above model, drip_speed is a variable that directly impacts the

coffee_machine flow/the rate at which coffee increases. Since it is a

free variable/not defined in terms of any other variables, it can be specified

during a model run to configure the simulation. We can run a couple simulations

and compare the final coffee stock values (at timestep 10):

>>> coffee_process(drip_speed=4.0).coffee.values[0, -1]

36.0

>>> coffee_process(drip_speed=1.0).coffee.values[0, -1]

9.0

Metrics#

Metrics are a special type of component whose equations run once, after all the

timesteps of the simulation have been calculated. These equations are normally

used to retrieve a specific value or run a basic analysis/measurement on

something. Metrics are useful from a convenience standpoint (making it

semantically simpler to get e.g. the last value of the coffee stock like in

the previous example), since they are then available to include in Reno’s

Visuzliations, but they can also be used as targets for observed/measured

values (“data”) for Bayesian Inference.

We can add a metric to the previous system to capture the final value in the stock with:

coffee_process.final_coffee_level = reno.Metric(coffee.timeseries[-1])

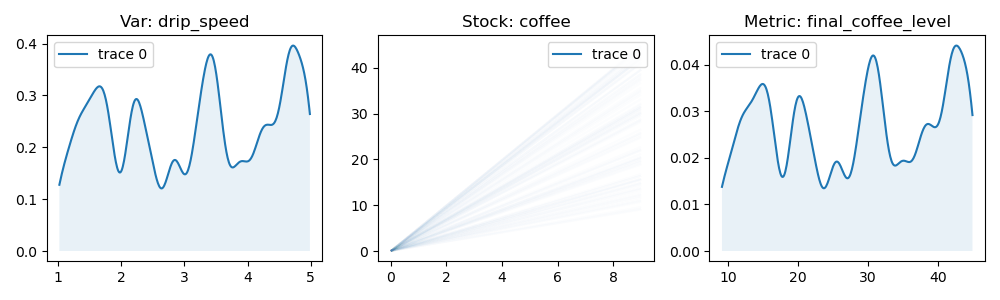

This would, for example, allow plotting this final value distribution if an

input distribution were specified for drip_speed:

>>> run = coffee_process(n=100, drip_speed=reno.Uniform(1.0, 5.0))

>>> reno.plot_trace_refs(

coffee_process,

[run],

[

coffee_process.drip_speed,

coffee_process.coffee,

coffee_process.final_coffee_level

],

rows=1,

cols=3,

figsize=(10, 3)

)

Other arguments for components#

min/max#

All stock/flow/variable components take several additional optional arguments.

Equation minimum/maximum limits can be defined with equations/values via min

and max. This can be useful to specify on outflows to avoid sending a stock into

negative values (e.g. if it represents a physical quantity.) In the coffee

example above, the coffee_machine flow is initialized with a max=water,

meaning that despite the result of the equation itself, the value won’t be

higher than the water stock in each timestep.

It is important to note that setting a min/max on a stock does not modify inflow values to that stock. To highlight this, the system below defines two stocks with a flow in between:

m = reno.Model()

with m:

s1 = reno.Stock(init=100)

s2 = reno.Stock(max=10)

f1 = reno.Flow(20, max=s1)

s1 >> f1 >> s2

s2 isn’t allowed to contain more than 10, but the inflow is pulling in 20 at

each timestep. Running this model for a few steps, we observe that s2 never goes

above 10, but s1 still decreases by 20 each time, resulting in “dropped” material.

>>> run = m(steps=3)

>>> run.s1.values[0]

array([100, 80, 60])

>>> run.f1.values[0]

array([20, 20, 20])

>>> run.s2.values[0]

array([0, 10, 10])

To appropriately bottleneck a stock like this entails also applying limits to the flow, possibly using something like the space operation discussed on the Math in Reno page.

dim/dtype#

Specifying the dtype (where you pass a regular python type such as float,

int, bool, etc.) of a component ensures the type of the underlying value and

will automatically convert as needed. This type assignment occurs on initial

value population - this either occurs automatically at the beginning of a

simulation, or you have to call populate() yourself:

>>> a = r.Variable(5, dtype=float)

>>> a.eval()

5

>>> a.populate(1, 1)

>>> a.eval()

5.0

Type information is automatically determined/broadcast when not explicitly specified, and converted appropriately when it is:

>>> m = r.Model()

>>> m.a = r.Variable(5)

>>> m.b = r.Variable(m.a)

>>> m.a.dtype, m.b.dtype

(int, int)

>>> m = r.Model()

>>> m.a = r.Variable(5, dtype=float)

>>> m.b = r.Variable(m.a)

>>> m.a.dtype, m.b.dtype

(float, float)

>>> m = r.Model()

>>> m.a = r.Variable(5, dtype=float)

>>> m.b = r.Variable(m.a, dtype=int)

>>> m.a.dtype, m.b.dtype

(float, int)

dim refers to an optional extra “data dimension” which allows you to work

with vector data. Operations automatically broadcast according to numpy rules

(TODO: link broadcasting):

>>> a = r.Variable(5, dim=4)

>>> a.eval()

array([5, 5, 5, 5])

Note that manually specifying dim only applies if the value is not already

vectorized:

>>> a = r.Variable([5, 2], dim=4)

>>> a.eval()

array([5, 2])

cgroup/group#

cgroup and group parameters are used for controlling diagram rendering,

see TODO: link to visualization cgroups page