Submodels#

Models can be split up, shared, re-used, and composed. Assigning a model as an attribute on another model (as if it were any other component) makes it a submodel. Some of the implications of having a submodel:

Diagrams show all the components of a given submodel within the same sub-graph, visually distinguishing and grouping them from the parent model.

Parameterizing the submodel in a parent model’s

__call__()is done by passing a dictionary containing the call parameters of the submodel.Submodel components will render with model name subtext in their latex equations.

Submodels are currently limited in operating on the same timescale/timesteps as if they were all within a single model.

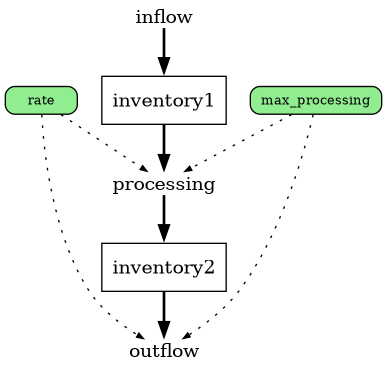

As an example, suppose there’s some generic chain of processing to turn a raw material into a processed material, with delay times and maximum amounts that can be processed and moved at once.

import reno

processing_chain = reno.Model()

with processing_chain:

# variables to control process

rate = reno.Variable(5)

max_processing = reno.Variable(10)

inventory1, inventory2 = reno.Stock(), reno.Stock()

inflow = reno.Flow()

# both the processing step itself and moving material out

# are controlled here by the processing/rate, a simplistic form of delay

processing = reno.Flow(reno.minimum(inventory1 / rate, max_processing / rate))

outflow = reno.Flow(reno.minimum(inventory2 / (rate - 1), max_processing / rate))

# hook up the stocks and flows

inflow >> inventory1 >> processing >> inventory2 >> outflow

This model by itself looks like:

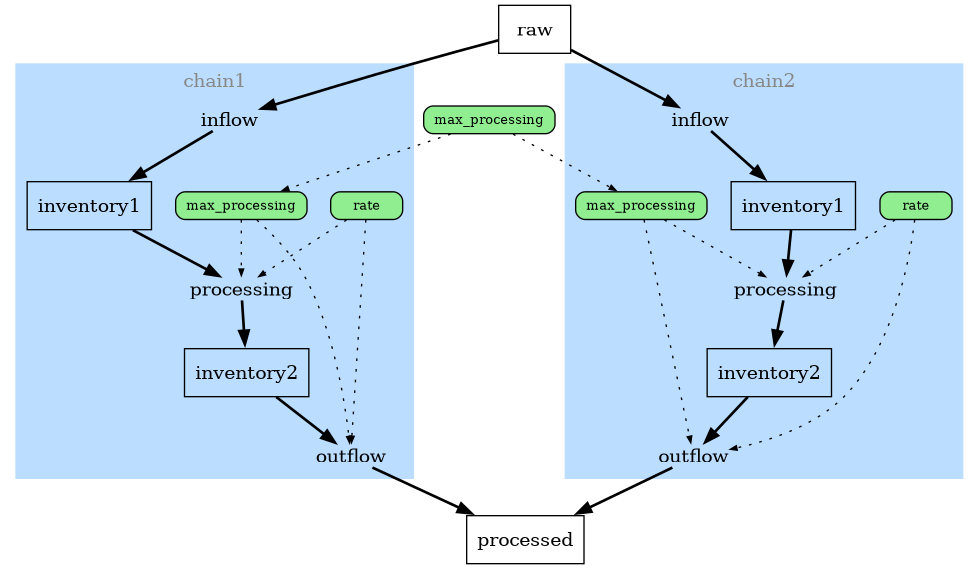

Suppose we want to have multiple of these chains running in parallel, possibly with different settings for the variables - we can do this by directly assigning copies of the model onto a parent model:

parent_model = reno.Model()

parent_model.chain1 = processing_chain.copy()

parent_model.chain2 = processing_chain.copy()

# change a parameter in just one of the chains

parent_model.chain2.rate.eq = 6

with parent_model:

# have a common max processing variable across both chains

max_processing = reno.Variable(15)

parent_model.chain1.max_processing.eq = max_processing

parent_model.chain2.max_processing.eq = max_processing

# both chains draw from a common beginning stock, and output to a

# common output stock

raw, processed = reno.Stock(init=100), reno.Stock()

parent_model.chain1.inflow << raw >> parent_model.chain2.inflow

parent_model.chain1.outflow >> processed << parent_model.chain2.outflow

# split beginning input up evenly between both chains

parent_model.chain1.inflow.eq = raw / 2

parent_model.chain1.inflow.max = max_processing / 2

parent_model.chain2.inflow.eq = raw / 2

parent_model.chain2.inflow.max = max_processing / 2

The full model diagram:

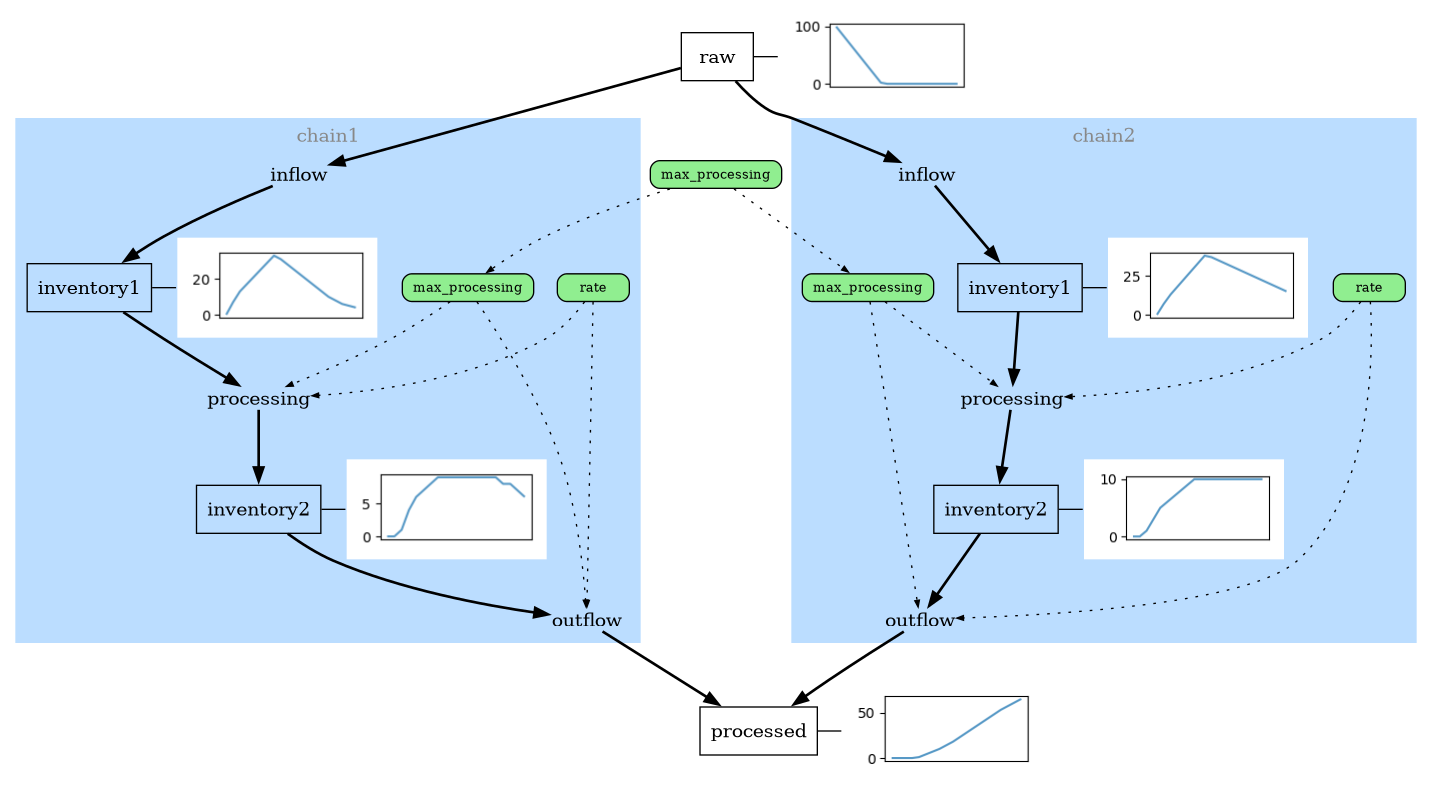

Running the parent model works as normal, with the exception that parameterizing any submodel free variables is done through a dictionary passed for the submodel name argument:

>>> ds = parent_model(steps=20, chain1=dict(rate=4))

>>> ds.attrs

{'max_processing': Scalar(15),

'raw_0': (= (= Scalar(100))),

'processed_0': 0,

'chain1.rate': Scalar(4),

'chain1.inventory1_0': 0,

'chain1.inventory2_0': 0,

'chain2.rate': Scalar(6),

'chain2.inventory1_0': 0,

'chain2.inventory2_0': 0}

Plotting the results with sparklines highlights the difference between the two separate submodels:

Dataset variables#

The dataset that gets returned from a run (or from model.dataset())

with submodels will prefix each submodel variable with the name of that model

(which is the name of the attribute it is assigned to on the parent model.)

The inventory2 stock for instance would be named chain1_inventory2 and

chain2_inventory2. This prefix still applies when getting the dataset of

the submodel directly, e.g. the variables in parent_model.chain2.dataset()

would still each be prefixed with chain2_.