Math in Reno#

TODO: this top paragraph feels like a good description of what Reno offers technically, move to main user_guide/main doc page?

A system dynamics model allows exploration of the behavior of a set of equations describing information or material flow over time. Reno provides a framework for creating and evaluating these equations similar to something like PyMC or PyTorch - symbolically setting them up in a form of compute graph that can then be populated with different values/data and run to create simulations.

The math API itself looks similar to numpy, but a lot of the functions are being added as I go/need them, if you need a numpy function that doesn’t yet exist in Reno, please submit an issue! (Or add them yourself locally in your project, see TODO: extending)

All aspects of models and their equations are made up of Reno’s

reno.components.EquationPart class, essentially a tree data

structure that can be made up of sub equation parts and has an

.eval() function to

populate and execute the equation compute graph.

Execution of an equation triggers recursive .eval() calls throughout the

full tree, each component running corresponding numpy operations

on the results from its sub-equation parts.

A simple example for an equation adding two constants is shown below:

>>> eq = reno.Scalar(3.0) + reno.Scalar(2.0)

>>> eq

(+ Scalar(3.0) Scalar(2.0))

>>> type(eq)

reno.ops.add

>>> eq.sub_equation_parts

[Scalar(3.0), Scalar(2.0)]

(Note that the repr for any equation part is a lisp-like prefix-notation string, this

is used and parsed for model saving/loading.)

eq in the code above is the “root” of an equation tree, in this case an addition

operation (reno.components.Operation is a subclass of

EquationPart) which has two child nodes (“sub equation parts”), each a constant scalar value.

No math has actually occurred yet, to execute you can run eq.eval(), which

recursively evaluates through the equation tree and returns the equation value. (A

Scalar simply evaluates to its assigned

value.)

>>> eq.eval()

5.0

Reno automatically converts constants into a Scalar when it sees them, so the

following are all equivalent:

>>> reno.Scalar(3.0) + reno.Scalar(2.0)

(+ Scalar(3.0) Scalar(2.0))

>>> reno.Scalar(3.0) + 2.0

(+ Scalar(3.0) Scalar(2.0))

>>> 3.0 + reno.Scalar(2.0)

(+ Scalar(3.0) Scalar(2.0))

(at least one Reno component/operation is required for this to work, otherwise Python just evaluates the math as normal.)

Operations#

Symbolic operations, like what’s shown above, are the core of how Reno’s math

system works. A full list can be found at reno.ops. Conceptually

Reno’s math is intended to act similarly to PyTensor (what PyMC uses under the hood),

though in our implementation acting as a thunk for Numpy operations, while providing

a way to translate directly into the PyTensor math system for TODO: link bayesian reasons.

Reno’s operations are a growing list of mappings to various numpy functions, but there are some special types of operations and considerations discussed below.

TODO: not sure where this belongs or if necessary, but a defense of why we’re “reinventing the wheel”:

Reno operations can be parsed from strings/supporting easy save/load and (possibly eventually) user entry

simpler to use and modify directly than PyTensor, at obvious cost of not being the hyper-optimized/compilation method that they enable/not having nearly the feature set they support

directly encodes how to compute both in numpy and in pytensor

simpler to build out custom operations

Reno is geared very specifically towards SDM, several considerations that merit having much more/easier control over equation compute graph/ability to parse and evaluate it in specific ways (e.g. component references, specific shape expectations, static values, etc.)

As shown above, Reno operations overload many common python operators

when Reno components are involved, (e.g. +, -, *, /,

%, <, >, <=, >=, &, |), but these operations (and

the rest) are subclasses of Operation and can all be used directly by

instantiating them with the appropriate operands:

>>> reno.Scalar(3) + reno.Scalar(2) - reno.Scalar(1)

(- (+ Scalar(3) Scalar(2)) Scalar(1))

>>> reno.sub(reno.add(3, 2), 1)

(- (+ Scalar(3) Scalar(2)) Scalar(1))

Timeseries and series operations#

Reno has several operations that work across a series rather than a single

sample value. These include reno.ops.series_min/reno.ops.series_max,

reno.ops.slice, reno.ops.sum, etc. These operations can

be applied directly to values that already have an additional dimension, (TODO:

link to components multidim) for example:

>>> reno.Scalar([1, 2, 3]).sum().eval()

6

>>> reno.Variable(5, dim=3).sum().eval()

15

The normal python indexing/slicing syntax with [] can be applied

to any EquationPart and it will be turned into the appropriate Reno

operation:

>>> my_scalar = reno.Scalar([1, 2, 3])

>>> my_scalar[1]

(index Scalar([1, 2, 3]) Scalar(1))

>>> my_scalar[1].eval()

array(2)

>>> my_scalar[1:3]

(slice Scalar([1, 2, 3]) Scalar(1) Scalar(3))

>>> my_scalar[1:].eval()

array([2, 3])

Series operations can also act across a component’s values over time, done by

running the reno.ops.orient_timeseries operation on the component,

or the more semantically friendly way by calling the component’s timeseries property. This is

often useful in Metric equations, but

it can also be used in flows/variables if a flow should be based on some set of

past values. Note that during a simulation run, the timeseries is the full

length of the simulation, but all values after the current timestep are populated

with 0’s.

>>> m = reno.Model()

>>> t = reno.TimeRef()

>>> with m:

>>> increase_over_time = reno.Variable(t + 2)

>>> total_accumulation = reno.Variable(increase_over_time.timeseries.sum())

>>> results = m()

>>> results.increase_over_time.values

array([[ 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]])

>>> results.total_accumulation.values

array([[ 2, 5, 9, 14, 20, 27, 35, 44, 54, 65]])

Historical values#

Related to the timeseries operation is the HistoricalValue component, retrieved through any component’s

history() function. This

allows specifying an index equation to retrieve a single previous value in that

component’s timeseries. For non-metric equations that don’t require slices from

the timeseries this approach should be

preferred, as any index equation that takes the form [TimeRef] - [static

value] results in a significantly simpler (and faster) PyMC output.

In general then, single previous timeseries values in stock/flow/variable equations should take the form:

t = reno.TimeRef()

my_flow.eq = my_stock.history(t - 3)

while any metric equations or stock/flow/variable equations that require more complex indexing or slicing should take the timeseries form:

t = reno.TimeRef()

some_var = reno.Variable()

my_flow.eq = my_stock.timeseries[t - some_var:t - 1].sum()

Broadcasting?#

Maybe this belongs in the components section?

Component references#

Extended operations#

Extended or “higher order” operations are any operations that wrap/abstract some set

of hidden sub-components or are based on other Reno operations in order to run

some more complex process. A simple example of this would be the

reno.ops.pulse operation, which returns a 1 for a specified number

of timesteps at a specified start time, and 0 at any other timestep. To achieve

this, it uses a Piecewise component rather than directly defining a

numpy/pytensor operation.

More complex examples include higher order material delays such as

reno.ops.delay1 and reno.ops.delay3, both of which

require using one or more “implicit”/inner stocks to allow accumulation of

material flowing through the op while ensuring none is lost (e.g. the total

amount of material that flows in = the total amount of material that eventully

flows out.) Components created in ExtendedOperation instances set a special implicit attribute to True, so that they

aren’t separately rendered in diagrams/latex equations etc.

Meta operations#

Meta operations are any that set up their underlying equations at runtime or instruct Reno to handle something in a specific way.

inflow#

reno.ops.inflow is a purely semantic operation that tells Reno to

treat a flow used in another flow equation as an “inflow”, as if it were a

stock. This doesn’t change the math or underlying equation, it only modifies how

the stock and flow diagram gets rendered – the thicker inflow/outflow line gets

applied to the flow to flow reference edge, which in some cases can help retain

consistency in visualizing how material is moving in the overarching structure.

As an example, suppose we have a system with two stocks, and two flows in between them:

m = reno.Model()

with m:

s1, s2 = reno.Stock(), reno.Stock()

f1, f2 = reno.Flow(), reno.Flow()

s1 >> f1

f2.eq = f1 - 1 # some material lost between s1 and s2

f2 >> s2

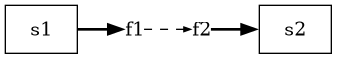

At a high level, stuff from s1 is flowing into s2 through f1 but

with some amount of loss in between, handled by f2. The thick material edges

from s1 moving to s2 is then shown indirectly, since Reno doesn’t know

if f2 is just referencing f1 in its equation, or modfiying it as an

inflow to s2. This indirectness is apparent in the diagram:

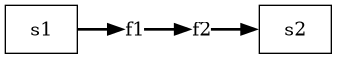

Wrapping a flow reference with inflow(), e.g. f2.eq = reno.inflow(f1) tells Reno to render the f1 -> f2 edge as a normal flow/stock line:

m = reno.Model()

with m:

s1, s2 = reno.Stock(), reno.Stock()

f1, f2 = reno.Flow(), reno.Flow()

s1 >> f1

f2.eq = reno.inflow(f1) - 1

f2 >> s2

Resulting in a more representative diagram:

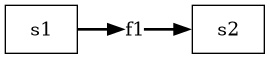

It is worth noting that for some situations this can also be achieved more

cleanly using Implicit stock in-flows, where f2 is entirely cut out

as an explicit flow, and the diagram renders more simply:

m = reno.Model()

with m:

s1, s2 = reno.Stock(), reno.Stock()

f1 = reno.Flow()

s1 >> f1

(f1 - 1) >> s2

with a more straightforward diagram:

outflows#

space#

Shape and type info#

(cover multidim here)