Getting Started#

Installation#

Reno’s package name is reno-sd (reno was already taken) and is available

on both PyPI and conda-forge.

To install via pip:

pip install reno-sd

To install from conda-forge:

conda install conda-forge::reno-sd

The module itself is called reno and is simply imported as:

import reno

Defining a model#

Create a model by instantiating the reno.Model class,

optionally providing a name, simulation sample settings (steps - how many

timesteps to run each sample for, and n - the number of samples to run in

parallel), and an optional doc description of the model.

import reno

tub = reno.Model()

# or alternatively with more detail:

tub = reno.Model("tub", steps=30, doc="Model water flowing in/out of a bathtub")

Note that steps and n can be modified when the model is run, this simply

sets the defaults.

Adding stocks, flows, and variables to the model can be done by directly setting attributes on the model to instantiated components.

t = reno.TimeRef() # TimeRefs are variables that always equal current timestep

# make a user-controllable variable for flow rate

tub.faucet_flow_rate = reno.Variable(6.0)

# make in and out flows

tub.faucet = reno.Flow(tub.faucet_flow_rate)

tub.drain = reno.Flow(reno.sin(t) * 2 + 4)

# make a stock to represent the accumulation of water

tub.water_level = reno.Stock()

# hook up the in and out flows to the stock

tub.water_level += tub.faucet

tub.water_level -= tub.drain

Note that since components may need to reference other components that haven’t

been created yet, the equations for flows and variables can be defined

separately from instantiation by setting the .eq attribute:

tub.faucet = reno.Flow()

tub.faucet_flow_rate = reno.Variable()

tub.faucet.eq = tub.faucet_flow_rate + 3

tub.faucet_flow_rate.eq = 5

For more info on how equations in Reno work and how to construct them, see TODO (math page)

Model with blocks#

It can be annoying to add a lot of components to a model, especially if the

model has a long variable name. Models can be used as context managers, and so

can be used in with blocks (similar to how PyMC models are conventionally

defined.) Any components defined within a model’s with block are automatically added to the

model using the components’ variable names when the context manager exits.

import reno

my_long_model_name = reno.Model()

with my_long_model_name:

faucet_rate = reno.Variable(6.0)

facuet = reno.Flow(faucet_rate + 3)

drain = reno.Flow(7.0)

water_level = reno.Stock()

drain.max = water_level

faucet >> water_level >> drain

# my_long_model_name now has component attributes like previous examples:

# my_long_model_name.drain

Note that the >> or << syntax as shown in the example above can be used

to simplify hooking up stock inflows and outflows, see

Defining stock equations for more details.

Inspecting a model#

The methods discussed below will be based on this example (which can also be found in the [LINK] notebook).

import reno

t = reno.TimeRef()

tub = reno.Model("tub", doc="Model the amount of water in a bathtub based on a drain and faucet rate")

with tub:

faucet, drain = reno.Flow(), reno.Flow()

water_level = reno.Stock()

faucet_off_time = reno.Variable(5, doc="Timestep to turn the faucet off in the simulation.")

faucet >> water_level >> drain

# the faucet should be some waterflow amount until the faucet is turned

# off, so we use a piecewise operation to make a conditional based on time

faucet.eq = reno.Piecewise([5, 0], [t < faucet_off_time, t >= faucet_off_time])

drain.eq = reno.sin(t) + 2

# the drain can't move negative water, and can't drain more than exists

# in the tub

drain.min = 0

drain.max = water_level

Stock and flow diagrams#

Once a model is created, there are a few different ways to see what it looks

like. A stock and flow diagram is the easiest way to see how everything is

connected in the model, and can be generated using the model.graph()

function.

tub.graph()

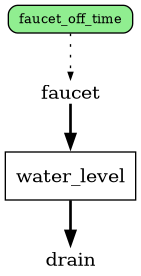

The stock and flow diagram of this model looks like:

In these diagrams, the rectangular boxes represent stocks, labels between arrows represent flows, and the green rounded boxes represent variables. The heavy solid arrows represent stock in/out flows, while dashed and dotted lines indicate which references are used in which other references.

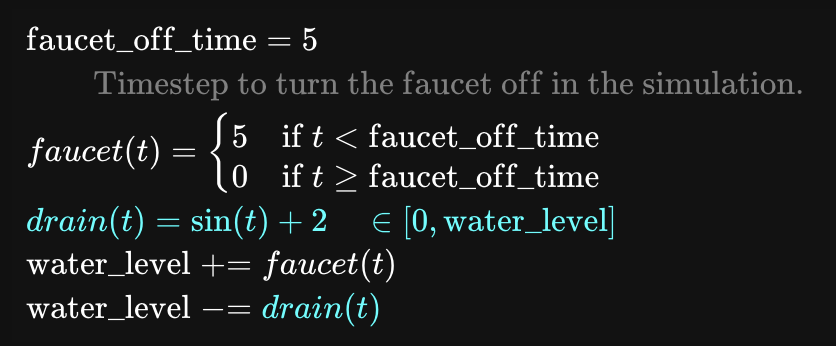

Latex equations#

A latex version of the equations for all of the stocks, flows, and variables can

be viewed with the model.latex() function.

By default this outputs (when running in Jupyter) an interactive widget with the

latex equations, and when clicking on any line, the reference name for that equation

line is highlighted everywhere else in the other equations. (This makes it

easier to track down where variables are used in very large systems.)

To get just a string version of the latex, pass raw_str=True.

Model docstring#

Models and every reference you add to models can be provided a doc

attribute, describing what the reference is/how to use it. All of this

information for a whole model can be compiled into a single Python-like

docstring using the model.get_docs()

function. This docstring shows how to configure and run the model, discussed in

the following section.

>>> print(tub.get_docs())

Model the amount of water in a bathtub based on a drain and faucet rate

Example:

tub(faucet_off_time=5, water_level_0=None)

Args:

faucet_off_time: Timestep to turn the faucet off in the simulation.

water_level_0

Running a model#

Once a model is defined, it’s time to run some simulations!

A model can be called like a function, with parameters for any free variables in

the system (including any initial values for stocks) and optionally

run-specific parameters such as the number of timesteps (steps) and the

number of instances to run in parallel (n).

In the model we defined above, there’s one free variable (faucet_off_time) and

a stock initial value, water_level_0 that can be set. (These can also be

found by running tub.free_refs(), which

returns a list of string names for the free variables/initial values.

Passing values for any of these are optional, the model will rely on values provided during definition if none are provided in the call itself.

To run one instance of the tub model with all default values, use:

results = tub()

To run five instances in parallel for a longer time and different configuration:

results2 = tub(n=5, steps=100, faucet_off_time=40, water_level_0=10.0)

The return from a simulation run is an XArray dataset, containing the values of every stock/flow/variable at each timestep.

>>> print(results)

<xarray.Dataset> Size: 336B

Dimensions: (sample: 1, step: 10)

Coordinates:

* sample (sample) int64 8B 0

* step (step) int64 80B 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Data variables:

water_level (sample, step) float64 80B 0.0 5.0 7.159 ... 10.45 7.457

faucet (sample, step) int64 80B 5 5 5 5 5 0 0 0 0 0

drain (sample, step) float64 80B 0.0 2.841 2.909 ... 2.989 2.412

faucet_off_time (sample) int64 8B 5

Attributes:

faucet_off_time: Scalar(5)

water_level_0: 0

As seen above, variables that are static values (e.g. faucet_off_time) don’t

include the step dimension, since they don’t change over time. A copy of the values

of each free variable in that run’s configuration are included in the

Attributes section of the output.

Running with distributions#

Running a model thus far with an n/samples more than 1 hasn’t made much sense since

these models are deterministic - each sample should run the exact same way. Samples come

into play when distributions are used in variables, which are randomly drawn from

for each sample (and optionally each timestep.) The simplest “distribution”

(which isn’t techncially a distribution) is reno.ops.List, which

simply iterates which item is selected for each sample, making it easier to

quickly test multiple variable values:

>>> tub.final_water_level = reno.Metric(tub.water_level.timeseries[-1])

>>> results = tub(n=3, faucet_off_time=reno.List([2, 4, 6]))

>>> results.final_water_level.values

array([ 0. , 2.456909, 12.456909])

Looking at the water level in the final timestep is now different in each sample, corresponding to the different faucet off time in each simulation.

Actually random distributions are currently available through:

As an example, we can run the tub model with a Normal distribution with mean 10 and a standard deviation of 5 with:

>>> random_results = tub(n=1000, faucet_off_time=reno.Normal(10, 5))

>>>

TODO: example with normal

Much more can be done with this, discussed further on the TODO: link bayes page.

Visualizing results#

TODO: links to the rest of the user guide